Art and Friendships: A Shared Cultural Experience

By Aditya Padinjat, UG’24 Cast your mind back to the first few days of college. The

By Mohan Rajagopal, UG’24

Trigger Warnings: Oppression, Violence, Nudity

Over the past few months, the student body of Ashoka University has been heavily engaged in the issues surrounding the coerced transfers of the housekeeping staff on campus. Numerous protests, demonstrations, sit-ins, and fundraisers were organised to support the non-teaching staff. Out of respect for the workers’ wishes, this article will not be delving into the details of these institutional shortcomings. However, the manner in which the movement has been mobilised across the University is something that is worth taking note of.

On the campus, different posters were put up in both English and Hindi to make the larger Ashokan community aware of the ongoing issues. In an email spam that the student body participated in, memes were also put to good use, mocking the apathy and indifference of the administration behind a facade of care and compassion. The use of both these media is immediately apparent: eye-catching designs and humorous images do well to grab the attention of a passerby, ensuring that they stop and absorb the information instead of ignoring it. Additionally, memes add a layer of relatability and accessibility, enabling a viewer to easily pass it on to someone else online and spread awareness through a viral image. This was especially important in a time when most of the student body is off-campus, giving rise to a need for a medium of protest that transcends physical boundaries.

Ashoka is not the only locale to weaponize these instruments: visual art has always played a vital role in political dissent, ranging from fine art to more localised, street art. Picasso’s Guernica, for instance, is one of the most famous examples of politically charged artwork, depicting the bombing of Guernica, a small town in Spain, by Germany and Italy during the Second World War. A Surrealist painting, the chaos and abstraction of the art piece do well to contribute to the suffering and violence, manifested by a screaming woman, a dead child, a mutilated soldier, and other symbols of war and devastation.

However, fine art itself was often considered a sign of oppression and inequality, representing the hierarchies and privileges of mainstream society. In opposition to this, arose the iconoclasm movement which aimed to destroy icons, images, and monuments, usually for religious or political reasons. Tracing its origins to the French Revolution, iconoclast rebels would often deface valuable works of art, and this vandalism was one of the earliest appearances of graffiti as we know it today. An iconic example would be the street art on the Berlin War, constructed in 1961 to separate East and West Berlin during the Cold War. The West Berlin side of the Wall was covered in graffiti and art, often admired by the tourists and passersby, while the East Berlin side remained completely blank as the citizens were not permitted to approach the Wall. The stark difference between the two sides served as a powerful reminder of the political contrast between the two regions. Today, the pseudonymous Banksy is probably the most famous street artist, using satire and dark humour in his art as socio-political commentary.

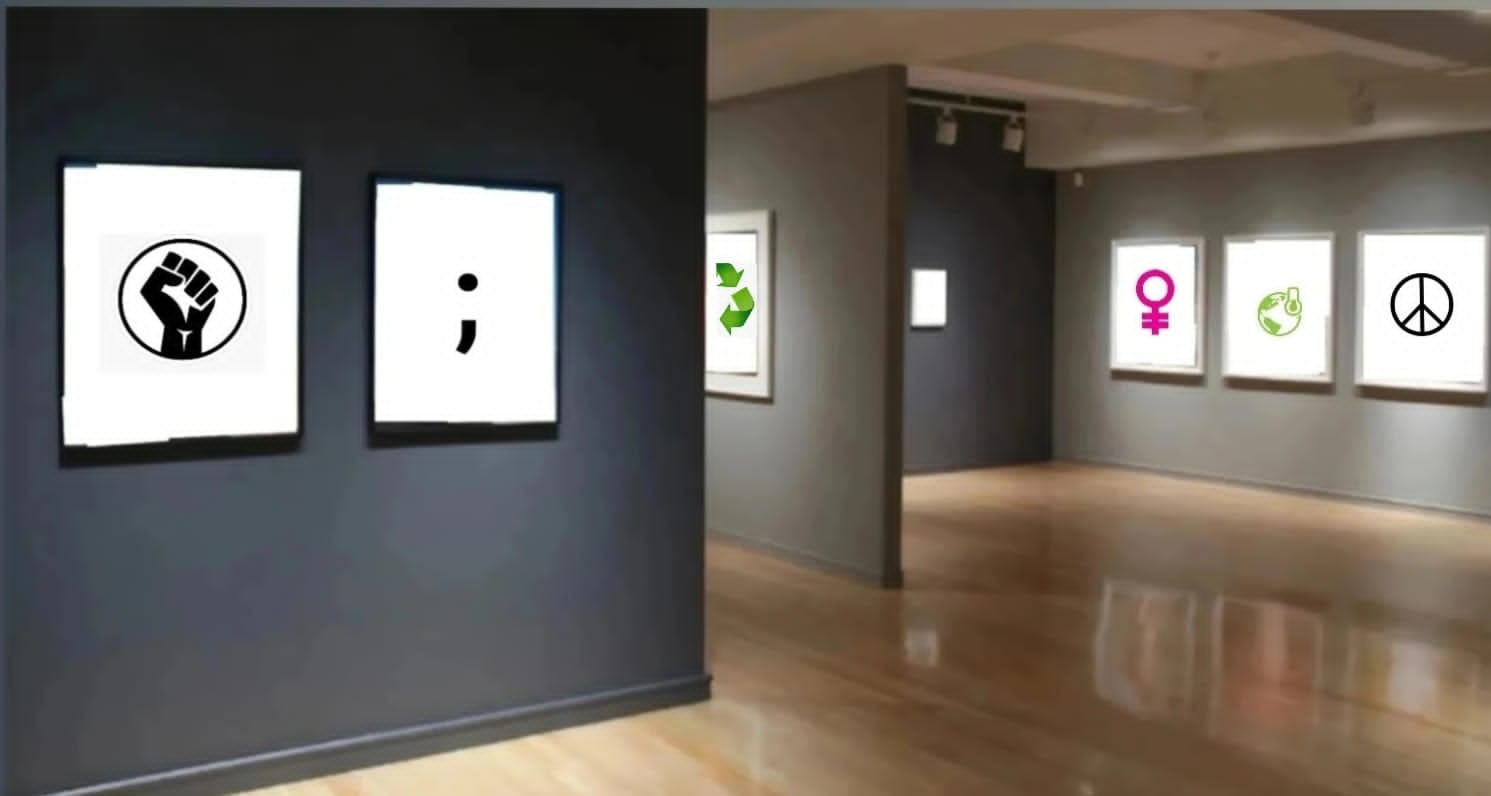

Over decades, as certain pieces of art are repeatedly used in conjunction with a particular social movement, they come to be regarded as symbols and icons of that movement. The raised fist as a symbol of the Black Lives Matter movement, as well as the rainbow as representative of the LGBTQIA+ community, are a few such icons that are instantly recognisable. However, this art need not be abstract or merely symbolic; even real-life photographs have come to be representative of various social upheavals or periods of time. The Napalm Girl (Trigger Warning: nudity, violence) is considered one of the most powerful images in the past century, featuring a naked child screaming and running after being injured by a napalm attack. The photograph by Nick Ut marked the end of the disillusionment of the American citizens by the war propaganda being fed to them, opening their eyes to the horrors faced in Vietnam.

The impact of such photographs and artwork could perhaps be greater than the role of protest literature and written material. It is undeniable that poetry, manifestos, and novels intended as political commentary can often be an inherently bourgeoisie phenomenon: inaccessible, convoluted, and concentrated amongst the wealthy. In contrast, one need not be well-versed in literary forms and styles or require any form of professional training to fully comprehend an image of violence. Visual art in protest is, hence, more accessible as it addresses the base instincts and forces the viewer to confront their human emotions of trauma and terror. As opposed to the purely aural or oral experience of protest literature, art provides its audience with a tangible manifestation of the system it is fighting against. The emotions that well up within the viewer leave a greater impression. In targeting society from its very grassroots, visual art mobilises a movement that is much more effective in trying to dismantle the mainstream and institutionalise a new order.