The Explorers|Dark Omens, Demon Possession, and Djinns: A magical experience like never before

Nishka Mishra, Undergraduate Batch of 2022 “The spirits had seized my house. They claimed my mother’s

Vandita Bajaj, Class of 2020

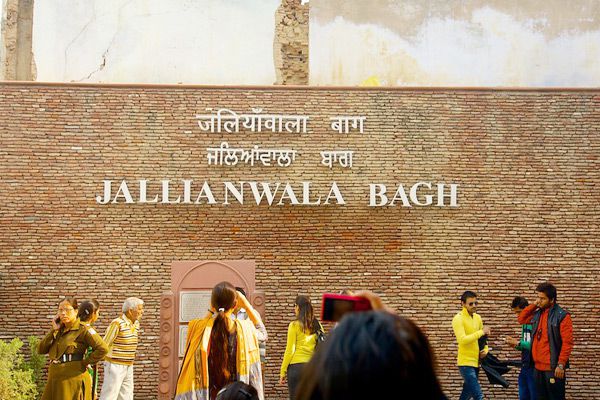

13th April 2019 marks the centenary of the Jallianwala Bagh massacre which took place on the occasion of Baisakhi, 13th April 1919. The event has found repeated mention in our school history textbooks and has been recreated on celluloid in iconic films like Richard Attenborough’s Gandhi. The atrocity of Jallianwala Bagh incident is that General Dyer ordered his troops to open fire on the peaceful gathering. But what were the pre-existing conditions that prompted this ruthless massacre and what were the repercussions noticed in the aftermath of what happened on the hot afternoon of 13th April 1919?

“A scar was drawn across Indo-British relations deeper than any which had been inflicted since the Mutiny”

-Percival Spear, Historian

WWI had ended but Indian support to the British war effort had not yielded in the attainment of independence. Punjab was especially rife with tension, reeling with the after-effects of widespread forced recruitment in the British Indian Army. The imposition of the Rowlatt Act, formulated by Sir Sidney Rowlatt under the leadership of Sir Sidney Rowlatt, was marked by widespread dissatisfaction and rebellion. Strikes and hartals organized to protest the actions of the British government — the undue restriction of civil liberties and basic rights — saw popular support and participation of Hindus and Muslims.

Thousands were flocking to Amritsar to celebrate the auspicious Baisakhi festival. The incoming masses were unaware of Michael O’Dwyer’s ban on public gatherings. A meeting was organized at Jallianwala Bagh to protest against the arrest of Dr Satyapal and Dr Saifuddin Kitchlew, who had been opposing the Rowlatt Act. Since the Jallianwala Bagh — it was an unused ground, enclosed on three sides by the backs of houses and a five-foot-tall wall on the fourth side — is a mere stone throw away from the Golden Temple, many of those visiting the gurudwara found their way to the site. And so did General Dyer and his troops — members of the 9th Gurkhas, 54th Sikhs and 59th Scinde Rifles — who opened fire on the gathering, there was no warning and everyone was a legitimate target. The firing is said to have gone on for eight to ten minutes, stopping only when the soldiers ran out of ammunition.

Salman Rushdie recounts the incident with accuracy in his book Midnight’s Children:

Brigadier Dyer’s fifty men put down their machine-guns and go away. They have fired a total of one thousand six hundred and fifty rounds into the unarmed crowd. Of these, one thousand five hundred and sixteen have found their mark, killing or wounding some person. ‘Good shooting,’ Dyer tells his men, ‘We have done a jolly good thing.’

The lack of remorse that Rushdie attributes to Dyer is glaringly noticeable in the testimony given by the General to his division command:

“If more troops had been at hand, the casualties would have been greater in proportion. It was no longer a question of merely dispersing the crowd, but one of producing a sufficient moral effect from a military point of view not only on those present, but more especially throughout the Punjab. There could be no question of undue severity?”

The reaction to the horrific event at the time was one of condemnation and called to question the very foundational ethos of British rule. Rabindranath Tagore renounced his knighthood, and wrote a scathing letter to the then Viceroy, Lord Chelmsford:

“…The disproportionate severity of the punishments inflicted upon the unfortunate people and the methods of carrying them out, we are convinced, are without parallel in the history of civilised governments… The time has come when the badges of honour make our shame glaring in their incongruous context of humiliation, and I for my part wish to stand shorn of all special distinctions, by the side of those of my countrymen, who, for their so called insignificance, are liable to suffer a degradation not fit for human beings…”

100 years on, Indians demand a formal apology from the British government, but only “deep regret” is offered. British Prime Minister, Theresa May described the incident as a “shameful scar” on British-Indian history, the acknowledgement was described as “inadequate” by many Captain Amarinder Singh, Chief Minister of Punjab. However, this demand for an apology overlooks the present situation in our own country — lynchings, the communal tension, the discriminatory treatment meted out to members of the LGBTQ community, the list goes on. The violence that is inflicted upon communities today stems far more from structural conditions, but its implications and impact demand introspection.

The author is the Managing Editor for the Arts and Culture Section of The Edict.